MICROSOFT FABRIC/POWER BI: DEEP DIVE INTO DIRECT LAKE ON ONELAKE

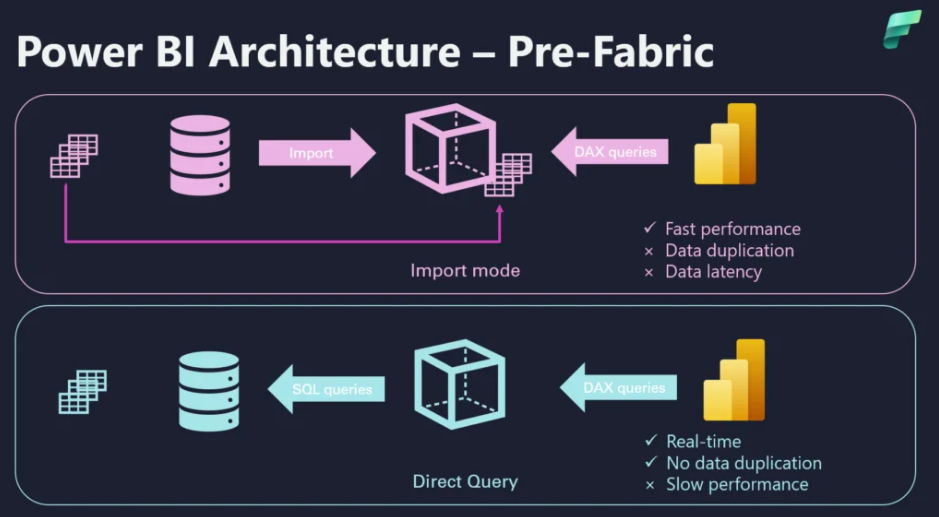

If you’ve ever had to choose between fast (Import) and fresh (DirectQuery) in Power BI, you know the trade-offs too well: long refresh windows on one side, laggy visuals on the other.

Source: data-mozart.com

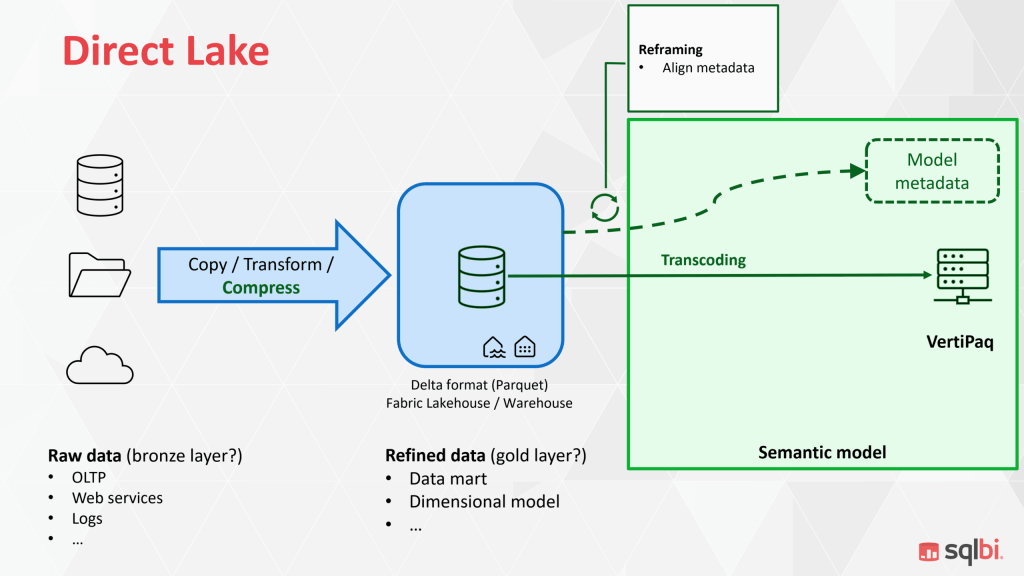

Direct Lake on OneLake promises a third path, which is near-Import query speed with near-real-time freshness, by allowing the VertiPaq engine to read Delta tables in OneLake directly, loading only the necessary columns. No duplicated “semantic-model copy,” no heavy complete refresh cycles, just a lightweight metadata update when your lake data changes.

This article is a practical deep dive into Direct Lake on OneLake. It won’t cover the SQL endpoint variant or its fallback behavior, that’s a different beast with different trade-offs. Instead, it will focus on the architecture and mechanics that matter for day-to-day BI: how OneLake + Delta + VertiPaq work together, what to expect in performance, what you must set up to succeed, where Direct Lake shines versus Import/DirectQuery (briefly), and the current limitations as of September 2025.

What is Direct Lake?

Direct Lake is a storage mode for Power BI semantic models that lets the VertiPaq engine read Delta tables in OneLake directly (from a Lakehouse) and hydrate only the columns it needs, when it needs them. Think of it as Import-like speed without pre-loading the whole dataset, and DirectQuery-like freshness without pushing every query down to a database.

Direct Lake also changes how “refresh” feels. Instead of re-ingesting and recompressing everything, a refresh is mostly a metadata reframe: the model simply points to the latest Delta version and invalidates the cache. After your pipelines land new data, a quick reframe (automated or via API) clears the way for VertiPaq to re-hydrate only what the next query needs. The result is near real-time freshness with in-memory responsiveness.

Why emphasize the Lakehouse? Because it enforces a clean “one copy of data” pattern: you optimize Delta once in the lake’s gold layer, and your semantic model reads those very files. You avoid second-stage ETL into a dataset, eliminate long and fragile refresh windows, and keep lineage crisp from Lakehouse → Model → Report. The trade-off is intentional: row/column security should be modeled at the semantic layer, and transformations you’d normally implement as calculated columns/tables in Import should instead be implemented in your ETL, keeping Direct Lake lean and predictable.

Architecture: OneLake – Delta – VertiPaq & How It Works

At a high level, Direct Lake on OneLake is a tight handshake between where data lives (OneLake + Delta) and how queries are executed (VertiPaq). The Lakehouse stores your (gold) tables as Delta files (Parquet + a transaction log). VertiPaq, the in-memory columnar engine behind Power BI semantic models, reads those files directly and materializes only the data required by the query.

The building blocks

OneLake (fabric-wide data lake)

OneLake is a shared storage fabric. Your Lakehouse sits here, organizing curated tables for analytics. Think of OneLake as the single, governed place where BI, data engineering, and data science all meet.

Lakehouse + Delta/Parquet

Each Lakehouse table is a Delta table: Parquet files (columnar, compressed) plus a _delta_log that tracks versions, adds, deletes, and schema changes. Delta’s ACID guarantees and versioning give BI a clean, atomic view of “the latest good state,” which matters when your pipelines are constantly landing data.

VertiPaq (Power BI’s storage engine)

VertiPaq is a memory-optimized, columnar engine. In Import mode, it preloads and compresses data ahead of time. In Direct Lake, it hydrates on demand from Delta files and keeps hot columns in RAM for subsequent queries.

V-Order

When your pipelines write Parquet in a VertiPaq-friendly layout, read performance improves, segments align with columnar scans, compression patterns suit VertiPaq, and fewer CPU cycles are wasted. The gist: optimize once in the lake, benefit everywhere.

Query lifecycle

- User interaction → DAX.

Dragging a visual produces a DAX query. The formula engine (DAX) shapes the request; the storage engine plans which columns, filters, and groups are needed.

- Column pruning & segment selection.

The storage engine prunes the request down to just the columns and row segments that matter. No table-wide reads.

- Direct file reads.

VertiPaq reads the necessary Delta/Parquet files from OneLake. Upon a column’s first touch, it transcodes the data into VertiPaq’s in-memory format (dictionary/encoding), then executes aggregations and joins.

- Caching in RAM.

Because the column is now warm, follow-up queries involving that column return with Import-like speed. If memory pressure rises, cooler columns can be paged out, because Direct Lake is designed for “bigger than memory” scenarios.

- Return to the visual.

The result flows back through DAX to your visual. From the user’s point of view, it feels like Import – without having paid the upfront import cost.

Framing

In Import, refresh means re-reading everything into the model. In Direct Lake, refresh is usually a metadata operation:

- ETL/ELT pipelines land new Delta files (and commit a new Delta version).

- The semantic model performs a reframe, which updates pointers to the latest Delta version and invalidates the cache.

- Subsequent queries hydrated from the new files, nothing was bulk-copied into the model.

Because only metadata and cache state are updated, freshness feels near real-time once pipelines complete, while maintaining high interactive performance.

Memory behavior and “column temperature”

VertiPaq maintains a working set of hot columns. Frequently used columns remain in memory; rarely used ones cool off and can be evicted. This design:

- let’s you analyze data volumes far larger than available RAM

- keeps costs predictable by materializing only what users actually query.

Warm-up is the only time you’ll typically notice overhead (that first touch of a column).

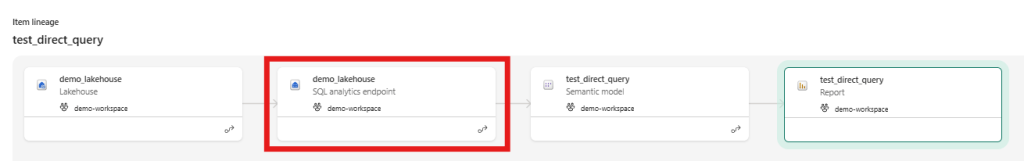

Direct Lake Item Lineage (DirectQuery vs Direct Lake)

A clean lineage story is one of Direct Lake’s biggest wins. Instead of hopping through external databases at query time, your report traces a short, governed path in Fabric: Lakehouse (Delta) → Semantic model (Direct Lake) → Report.

Traditional DirectQuery report

The report connects to a semantic model in DirectQuery mode. Each interaction is translated and sent to the Lakehouse SQL analytics endpoint. The endpoint executes the query against the Lakehouse (backed by Delta/Parquet in OneLake). Performance and availability are tied to the SQL endpoint and the underlying Lakehouse I/O at run time. Because this SQL endpoint is an extra hop, it causes additional latency compared to Direct Lake (OneLake Connection).

Direct Lake report (OneLake connection)

The report connects to a Direct Lake semantic model that reads Delta/Parquet in OneLake from a Lakehouse. Upstream pipelines/notebooks land and optimize Delta files. “Refresh” is a framing step (metadata switch to the newest Delta version), not a bulk re-ingest.

DirectQuery’s Hidden Costs

- Runtime latency vs. Direct Lake. Each click is translated to SQL and executed on the Lakehouse SQL analytics endpoint. Microsoft notes that query processors behind DirectQuery are often not optimized for BI-style aggregations, which is why DQ can feel slower and less interactive than Import/Direct Lake.

- Metadata sync lag. The endpoint maintains its own metadata over your Delta tables. Under normal conditions the lag is < 1 minute, but it can stretch to minutes depending on workload. Lots of small files / over-partitioning increases sync time. You can force a metadata refresh in the UI or via REST.

- Throughput & concurrency. The endpoint has its own performance guidelines and limits (concurrency, throttling behavior).

Data contracts: what a “good lake” looks like

Direct Lake makes the lake’s quality visible to end users. To keep queries fast and predictable, treat your Lakehouse tables as contracts:

- Stable schema with explicit data types.

- Partitioning that matches query patterns (typically by date/time).

- Compact Parquet files of sensible size, avoid “small files” explosions by regularly compacting/optimizing.

- Column order/encoding friendly to scanning (and write in V-Order when available).

- Push transformations you’d normally implement as calculated columns/tables down into ETL, so the semantic model stays lean.

A quick comparison with Import and DirectQuery

Suppose Import is about preloading everything for speed, and DirectQuery is about asking the source every time for freshness. In that case, Direct Lake (on OneLake) aims for the middle ground: near-Import interactivity with near-real-time freshness, without duplicating data into a semantic-model cache. Here’s a quick comparison table of the three connection modes.

| Aspect | Import | Direct Lake (OneLake connection) | DirectQuery |

| Query feel | Fastest (already in RAM) | Near-Import after warm-up | Slowest; depends on source |

| Freshness | On refresh schedule | Near real-time (metadata reframe) | Real-time (source of truth) |

| Data copy/ops | Duplicates into model; heavy refresh | No second copy; light “reframe” | No copy; pushes load to source |

| Modeling features | Full (calc cols/tables, Power Query etc.) | Some limits (calc cols/tables in ETL) | Full model logic, but source-bound |

| Source flexibility | Any source via Power Query | Delta in OneLake (Lakehouse) | Many DB/warehouses with connectors |

| Scale vs RAM | Must fit (or large-model tricks) | “Bigger than memory” via on-demand | Source scales; BI latency grows |

Current limitations (as of September 2025)

Before we wrap, a reality check: Direct Lake on Lakehouse is powerful, but it’s not limitless. A few constraints still matter for real-world design and operations. Below are the high-impact limitations you should plan around as of September 2025.

- No DirectQuery fallback in the OneLake flavor: if you hit an unsupported construct or a guardrail, the query errors (it won’t auto-switch to Direct Query).

- Calculated columns/tables that reference Direct Lake tables aren’t supported: this logic needs to be pushed into the logic into upstream ETL/ELT or non-Delta Lake tables.

- Sources: non-materialized SQL views aren’t supported for Direct Lake on OneLake, and Lakehouse shortcuts are not supported during public preview (suggest using MLVs).

- Security: SQL-endpoint RLS doesn’t apply when reading files directly: the user needs to define RLS/OLS at the semantic model instead.

- Capacity guardrails: exceeding limits (e.g., >10,000 Parquet files per Delta table) can cause framing to fail; there’s no DirectQuery fallback in OneLake, so you must compact/optimize or resize.

- Region binding: you can’t create a Direct Lake model from a Lakehouse in a different region (workaround: create a Lakehouse in the target region, then shortcut before modeling).

Conclusion

Direct Lake on Lakehouse gives you a pragmatic third path between Import and DirectQuery: Import-like interactivity after warm-up, near-real-time freshness via metadata reframing, and a “one copy of data” architecture that keeps pipelines and lineage clean.

Crucially, Direct Lake is not a wholesale replacement for Import or DirectQuery. It’s an additive option—one that can replace Import or DirectQuery in the right contexts but should sit alongside them in your toolkit. The job is to match the mode to the workload, not to force-fit the workload to the mode.