Hashing Function and Message Digests

- A hash function compresses data

- A message digest represents it

What is a Hash Function?

Mathematically, a Hash Function is a deterministic algorithm that maps an input of arbitrary size to a fixed-size output string. This transformation is formally represented by the following mapping:

H : {0,1}* → {0,1}^n

- {0,1}* : Represents the Input Space (Domain). It consists of bit strings of arbitrary length—ranging from a single character to the entire contents of a massive digital library.

- {0,1}^n: Represents the Output Space (Range). The result is always a bit string of a fixed length n (for example, n = 256 bits in the case of SHA-256).

- Hash Value (Digest): The output h = H(x) is commonly referred to as a “digital fingerprint” of the input data.

What is a hash function used for?

In the realm of security engineering, a hash function is often called the “Swiss Army Knife” of cryptography. It isn’t just a theoretical concept; it is the silent engine powering almost every security protocol we use today.

Here are the primary applications of hash functions:

1. Data Integrity Verification

This is the most fundamental use case. When you download a large file or transmit data over a network, how do you know it hasn’t been corrupted or tampered with by a man-in-the-middle?

- The Mechanism: The sender calculates h = H(data) and provides the hash value alongside the data. Upon receipt, the recipient re-calculates H(data_{received}).

- The Logic: If the two hashes match, the data is intact. Due to the avalanche effect, even a 1-bit change in the input will result in a completely different hash output.

2. Secure Password Storage

A golden rule in security: Never store passwords in plaintext. The Mechanism: Instead of storing a password like “P@ssword123”, a system stores H(“P@ssword123” + Salt).

- The Benefit: If a database is leaked, attackers only see meaningless hashes. Because a cryptographic hash is a one-way function (Pre-image Resistance), it is computationally infeasible to reverse-engineer the original password from the hash.

3. Digital Signatures

Digital signature algorithms (like RSA or ECDSA) are computationally expensive. Signing a 1GB file directly would be incredibly slow.

- The Mechanism: Instead of signing the entire file, the system hashes the file to produce a small, fixed-length digest, and the signer applies their Private Key only to that digest.

- The Benefit: This dramatically increases performance while ensuring that the signature remains uniquely tied to the specific content of the file.

4. Message Authentication (MAC & HMAC)

As we discussed earlier, a simple hash only detects accidental changes. To prove that a message is both authentic (comes from a trusted source) and integral (hasn’t been changed), we combine a hash with a secret key.

Use Case: This is the industry standard for securing API requests and Webhooks (e.g., GitHub or Stripe Webhooks).

5. Unique Identifiers and Data Structures

In distributed systems and version control, hashes serve as the ultimate “name” for data:

- Git Commits: Every commit in Git is identified by a SHA-1 hash of the file contents and metadata. It ensures that the history of your code cannot be altered without changing the commit ID.

- Merkle Trees: Used in blockchain and file systems (like ZFS), Merkle Trees use hashes to efficiently verify the integrity of massive datasets.

The Three Pillars of Cryptographic Hash Functions

For a hash function to be considered “cryptographically secure,” it must satisfy three fundamental properties. These properties ensure that the “digital fingerprint” remains unique and irreversible.

1. Pre-image Resistance

Definition: Given a hash h, it is computationally infeasible to find any message m such that hash(m) = h

m ──hash──▶ h

❌ h ──?──▶ m

Security implications:

– This is the foundation of Secure Password Storage. Even if a database of hashes is leaked, attackers cannot reverse the hashes to find the actual passwords.

– Password protection

– Protecting tokens, keys, and file integrity

Attack Difficulty:

– With an n-bit hash, a brute force attack requires 2^n attempts

2. Second Pre-image Resistance

Definition: Given a message m1, it is infeasible to find a different message m2 such that hash(m1) = hash(m2)

m₁ ──hash──▶ h

❌ m₂ ≠ m₁ ──hash──▶ h

Security Impact:

– This property protects Digital Signatures and File Integrity. It ensures that once a file is hashed and signed, an attacker cannot provide a malicious file that produces the same signature.

Attack Difficulty:

– A second pre-image attack on an n-bit hash function requires approximately 2^n operations.

3. Collision Resistance

Definition: It is infeasible to find any two different messages m1 and m2 such that hash(m1) = hash(m2)

m₁ ──hash──▶ h

m₂ ──hash──▶ h (m₁ ≠ m₂)

Security implications:

– Digital signature

– Certificate

– Blockchain

– Integrity checking

Attack Difficulty:

– The Birthday Attack: Although an n-bit hash function has an output space of 2^n, to find two different inputs for the same hash value (collision), an attacker only needs about 2^(n/2) trials.

| Algorithm | Output Length (n) | Collision Security (n/2) | Status |

| MD5 | 128 bits | 64 bits | Broken. 2^64 is reachable by modern GPU clusters. |

| SHA-1 | 160 bits | 80 bits | Deprecated. Collisions were famously found by Google in 2017 (SHAttered). |

| SHA-256 | 256 bits | 128 bits | Secure. 2^128 is computationally impossible for the foreseeable future. |

Hash function don’t hide data -> It bind data

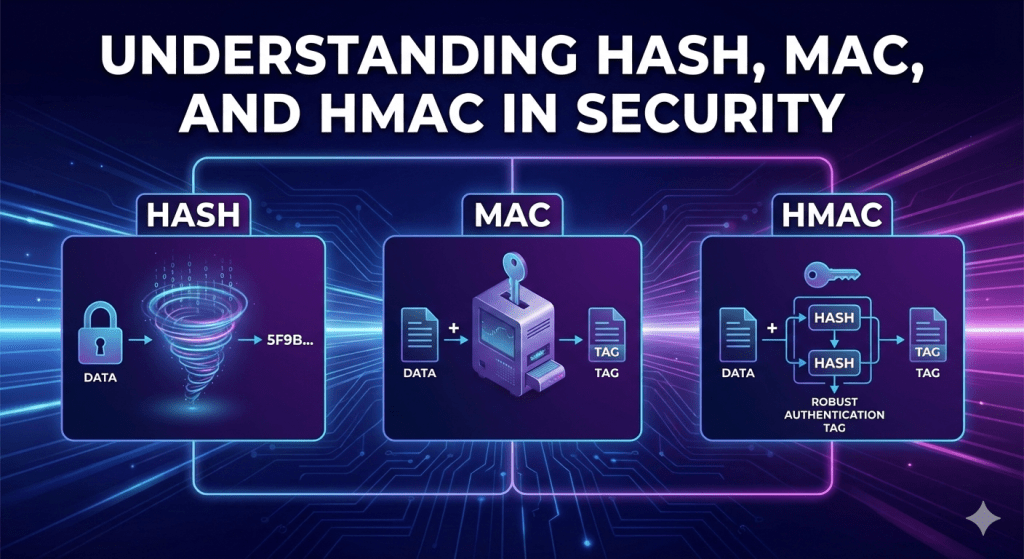

Message Authentication Code (MAC)

There is a fundamental distinction in security that you must understand: Integrity is not the same as Authenticity.

1. Integrity: “Has the data changed?”

– A simple hash function provides Integrity. It tells you if the data has been altered—usually by accident (like a corrupted download or a disk error). If the hash matches, the bits are the same.

2. Authenticity: “Who actually sent this?”

– A hash function cannot provide Authenticity. It has no way of verifying the source of the message. In the world of cryptography, a hash is a public tool; anyone with the same data can generate the exact same hash.

To fix this, we need a mechanism where only someone with a Secret Key can generate a valid tag. This turns a simple “checksum” into a “cryptographic proof of origin.”

Hash: Anyone can create it.

MAC: Only those who possess the shared secret key can create it.

If anyone receives a message and a valid MAC, they knows two things:

- The message was not changed (Integrity).

- The recipient can be certain the message originated from a party in possession of the secret key, as it is computationally infeasible for any other entity to produce a matching tag.

| Sender: tag = MAC(key, message) send (message, tag) Receiver: verify MAC(key, message) == tag |

=> MAC (Message Authentication Code) is a general concept:

MAC ensures that messages cannot be modified and originate from the person who owns the secret key.

Core Objectives:

– Origin Authentication: Proves that the message was indeed sent by the party who holds the secret key.

– Data Integrity: Ensures that the data has not been altered during transit.

– Tamper Detection: If even a single bit of the message or the key changes, the resulting MAC will be completely different, allowing the receiver to detect and reject the message.

Important Note: Avoid Length Extension Attacks

Length Extension Attacks occur with several Merkle-Damgård construction – type hash functions such as:

– MD5

– SHA-1

– SHA-256

– SHA-512

Thus, use HMAC if you want to use SHA-2 and use KMAC if you prefer SHA-3.

What is a MAC used for?

In modern security engineering, a Message Authentication Code (MAC) is the cornerstone of “Trust but Verify.” While encryption hides data, a MAC ensures that the data you are looking at is exactly what the sender intended.

Here are the most critical real-world applications of MACs:

– API Authentication and Webhooks

– Secure Cookie and Session Management

– Network Protocols (TLS, IPsec, SSH)

– Secure Boot and Firmware Updates

– Authenticated Encryption (AEAD)

The 3 Main Variants of Message Authentication Codes (MAC)

While the goal of every MAC is the same—to provide integrity and authenticity—the “engine” inside them differs. Choosing the right variant depends on your performance requirements and available hardware.

Hash-based MACs

HMAC is the most widely used variant in the world today. It leverages existing cryptographic hash functions (like SHA-256 or SHA-3) to create a MAC.

Advantages:

– Very secure

– Easy to implement

– Standardized (RFC 2104)

– Does not depend on block ciphers

Disavantages:

– Slightly slower than CMAC (due to hashing)

– Does not provide encryption

How it works: Instead of just hashing a key and message together (which is vulnerable to Length Extension Attacks), HMAC uses a “nested” structure with inner and outer padding (ipad and opad):

HMAC(K, M) = H( (K ⊕ opad) || H((K ⊕ ipad) || M) )

Pros: Extremely secure, well-studied, and easy to implement using standard libraries.

Common Uses: API Authentication (Stripe/GitHub), JWT (JSON Web Tokens), and TLS.

Block Cipher-based MACs

If your system already uses a block cipher like AES, it often makes sense to use that same engine to generate your MAC. This is what CMAC (specifically a refined version of the older CBC-MAC) does.

Advantage:

– Based on AES (fast, with hardware acceleration)

– Secure with messages of any length

– Standardized (NIST SP 800-38B)

Disadvantage:

– More complex than HMAC

– Dependent on block cipher

How it works: It processes the message in blocks using a block cipher. CMAC fixes the security flaws of the original CBC-MAC (which was insecure for variable-length messages) by using “subkeys” to process the final block.

Pros: Ideal for constrained environments (like IoT or embedded systems) that have hardware acceleration for AES but limited memory for additional hash functions.

Common Uses: Automotive security (CAN bus), disk encryption, and industrial IoT protocols.

Universal Hash-based MACs (UHF-MACs)

This is the “high-performance” category of MACs. Instead of relying on heavy-duty hashes or block ciphers for every byte of data, they use fast mathematical operations (polynomial evaluation over a finite field).

Features:

– Very fast

– Strong security (strong theoretical proofs)

– Requires no key reuse

The Big Names: GMAC (used in AES-GCM) and Poly1305 (used in ChaCha20-Poly1305).

How it works: They treat the message as coefficients of a polynomial and evaluate it at a secret point.

Pros: Incredibly fast, especially in software. Unlike HMAC or CMAC, these can be parallelized or computed with very high throughput on modern CPUs.

Common Uses: Google and Apple’s mobile traffic (Poly1305), modern web browsing (AES-GCM), and WireGuard VPN.

Conclusion: The Guardians of Integrity and Authenticity

We have traveled from the mathematical foundations of Hash Functions—the “digital fingerprints” that ensure your data remains untouched (Integrity) — to the robust protection of MACs and HMACs, which act as a shield verifying exactly who sent the data (Authenticity).

At this point, your security architecture can confidently answer two vital questions:

- “Has this data been tampered with?” (Integrity)

- “Did this data truly come from a trusted source?” (Authenticity)

The Missing Piece: The Secret

However, if you look closely at everything we have covered, there is a fundamental limitation: Neither Hashing nor HMACs hide your data. Imagine sending a letter. HMAC ensures the recipient knows the letter is from you and hasn’t been swapped, but every person handling that letter can still open it and read the contents. In the world of cybersecurity, we have built a wall to protect the truth, but we haven’t yet found a way to hide our secrets in plain sight.

How do we make our messages completely unreadable to eavesdroppers, only to have them “come back to life” for the intended recipient?

This is where we meet the final piece of the security triangle: Confidentiality.

Coming up next: In our next post, we will dive into Symmetric Encryption. We will explore how algorithms like AES transform your data into an unbreakable maze that only those with the right key can navigate. Stay tuned!

References:

- https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/hash-functions

- https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/message-authentication-codes

- Real-World Cryptography – David Wong

- The Handbook of Applied Cryptography – Scott Vanstone, Alfred Menezes, Paul van Oorschot